There are few devices that better exemplify the breakneck pace of modern technical advancement than the mobile phone. In the span of just a decade, we went from flip phones and polyphonic ringtones to full-fledged mobile computers with quad-core processors and gigabytes of memory.

While rapid advancements in computational power are of course nothing new, the evolution of mobile devices is something altogether different. The Razr V3 of 2003 and the Nexus 5 of 2013 are so vastly different that it’s hard to reconcile the fact they were (at least ostensibly) designed to serve the same purpose — with everything from their basic physical layout to the way the user interacts with them having undergone dramatic changes in the intervening years. Even the network technology they use to facilitate voice and data communication are different.

100vw, 400px”></a><figcaption id=) Two phones, a decade apart.

Two phones, a decade apart.Yet, there’s at least one component they share: the lowly SIM card. In fact, if you don’t mind trimming a bit of unnecessary plastic away, you could pull the SIM out of the Razr and slap it into the Nexus 5 without a problem. It doesn’t matter that the latter phone wasn’t even a twinkling in Google’s eye when the card was made, the nature of the SIM card means compatibility is a given.

Indeed there’s every reason to believe that very same card, now 20 years old, could be installed in any number of phones on the market today. Although, once again, some minor surgery would be required to pare it down to size.

Such is the beauty of the SIM, or Subscriber Identity Module. It allows you to easily transfer your cellular service from one phone to another, with little regard to the age or manufacturer of the device, and generally without even having to inform your carrier of the swap. It’s a simple concept that has served us well for almost as long as cellular telephones have existed, and separates the phone from the phone contract.

So naturally, there’s mounting pressure in the industry to screw it up.

Home is Where the SIM Is

With landline telephones, it was “easy” to figure out if the bill was paid. The carrier knew where each subscriber lived, and they knew where the phones were installed. The homeowner either paid the bill and got service, or they were cut off. Even when the earliest mobile phones started hitting the market, their large size and high cost meant keeping track of who owned them wasn’t too difficult.

But as mobile phones became smaller, cheaper, and more widespread, it was clear some method of authentication would be required to prove the user had an active account. Since the physical location of the phone could no longer be used to determine who owned it and what number it should get, it would be necessary to give each mobile phone its own unique ID number. Further, since it was inevitable that the subscriber would eventually get a new mobile phone, it made sense to tie their information to some removable storage device so it could be moved between devices.

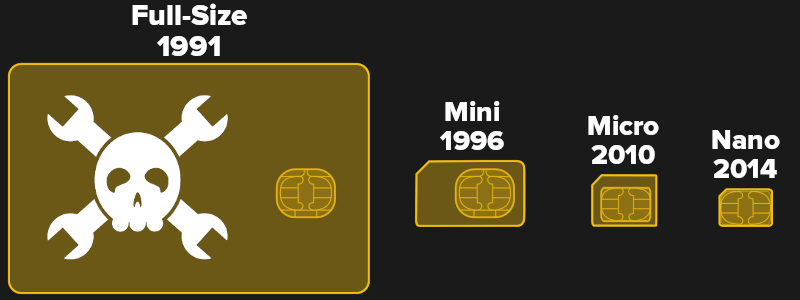

Thus, the Subscriber Identity Module was born. First introduced in 1991, the SIM card was actually envisioned as a way to carry the subscriber’s entire “digital life” between devices. It featured enough storage capacity to hold the user’s contact list and messages, which would be carried over to whatever new device the SIM was installed in. This concept has been all but abandoned today, as not only is the SIM’s storage capacity (less than 0.5 MB) laughable by modern standards, but we now have the cloud to allow seamless syncing between devices.

Modern SIMs are used almost exclusively to hold data necessary for network authentication. This consists primarily of the Integrated Circuit Card Identifier (ICCID), which is the SIM’s own serial number, and the subscriber’s account number, officially known as the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI). The IMSI includes identifying codes for which country and network the card is to be used on, as well as the subscriber’s phone number. In addition, the SIM contains a unique 128-bit authentication key that is checked against the carrier’s database when the device attempts to join the network. Naturally this is all an oversimplification — [LaForge] gave a fantastic talk on the nuts and bolts of SIM cards at 36C3 if you’ve got an hour to spare.

100vw, 400px”></a><figcaption id=) Nano-SIM with Micro and Mini adapters.

Nano-SIM with Micro and Mini adapters.The first generation SIM cards were the same dimensions of a credit card, and generally were installed in car phones and other large portable telephones. By the time 2G cellular technology was mainstream, phones were much smaller and were using what at the time was called a Mini-SIM. For many years this second form was the defacto form of SIM, to the point that most people think of it as the original. But ever-shrinking smartphones necessitated something even smaller. This lead to the adoption of the Micro-SIM in 2010, followed by the Nano-SIM in 2012.

Interestingly the size of the SIM card was dictated by ISO/IEC 7810, an international standard for the size and shape of identification cards, rather than the internal electronics. Each version of the SIM has utilized essentially the same active components, just mounted to smaller and smaller PVC cards. This allows the larger cards to be cut down to fit devices which use the smaller forms, while the smaller versions can be used in older devices by way of an adapter.

Understanding the design of the SIM card and its various forms, it’s clear that the Nano-SIM is the end of the road. There’s only enough of the PVC card material left to orient the chip in the holder — any less, and you’d have to cut the chip itself, which could potentially break decades of backwards compatibility.

So how do you make the a SIM even smaller? Easy. You get rid of it.

Breaking the Nano Barrier

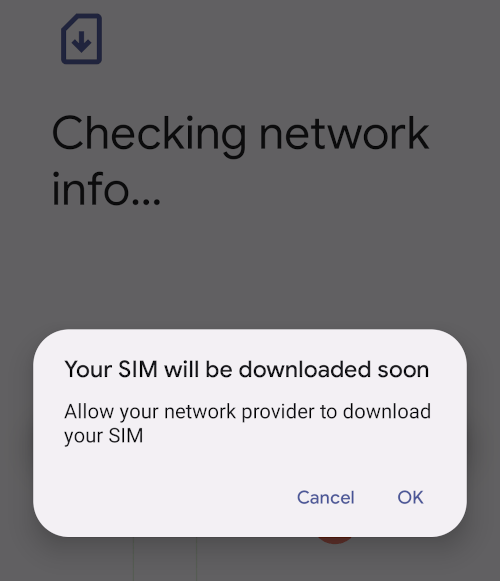

More and more phones today support what’s known as an Embedded-SIM (eSIM), which as the name implies, is built directly into the device. In practice, there’s still a dedicated flash chip that hold’s the subscriber’s information, the user just can’t get to it. But for some devices, such as a smartwatch, even an eSIM might be too large. In that case, there’s growing interest in Integrated-SIM (iSIM). With iSIM, the physical component is removed entirely — instead a sort of virtual SIM is integrated directly into the device’s System-On-Chip.

While most phones still offer Nano-SIM compatibility in addition to eSIM, the clock is ticking. Apple has already done away with physical SIM support as of the iPhone 14, and if history is any indicator, other manufacturers will soon follow. As of right now iSIM is being marketed towards wearables and IoT devices, but it’s not hard to predict that phone manufacturers will eventually be interested in the technology.

Who’s SIM is it Anyway?

With no physical SIM to remove, accessing and changing the data on the eSIM/iSIM must be done through the device’s own software. Naturally this means that not only will it require the latest-and-greatest version of your mobile operating system of choice, but that it’s possible for your device manufacturer or even carrier to control your access to it. Just as some carriers disable the option to unlock the bootloader on Google’s Pixel phones, one can imagine a future in which carriers will require you go through them every time you move your eSIM to another device.

In fact, there’s some scenarios in which you’ll almost certainly have to contact your carrier. Bust up your current phone bad enough that you can’t perform the self-serve eSIM swap? You’ll need to get the carrier to do it remotely. Want to switch eSIM between iPhone and Android? You guessed it, call the carrier and have them do it remotely.

In fact, there’s some scenarios in which you’ll almost certainly have to contact your carrier. Bust up your current phone bad enough that you can’t perform the self-serve eSIM swap? You’ll need to get the carrier to do it remotely. Want to switch eSIM between iPhone and Android? You guessed it, call the carrier and have them do it remotely.

To be fair, there are some potential security benefits to eSIM/iSIM. For one thing, you don’t have to worry about somebody stealing the SIM from your phone or replacing it with another one while you aren’t looking, because its not a physical object. Of course, that’s right now — who is to say a piece of malware couldn’t be crafted down the line to extract the subscriber information from the hardware?

In any event, it seems inevitable that the consumer won’t have much say in the matter going forward. Sure you can avoid buying a phone without a SIM card slot in 2023, 2024, and probably even 2025. But just as fewer and fewer phones each year still include a headphone jack, your options will eventually become limited. The day is coming when you’ll have to bid your trusty SIM card goodbye, and that’s a shame.

Source: https://hackaday.com/2023/03/20/the-rise-and-eventual-fall-of-the-sim-card/